A little help over here? A user attempts to wrestle open data into submission

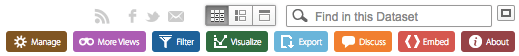

First, to sing a few praises: New York City’s Open Data portal has more than 1500 datasets available, and their tool allows you to sort, filter, and manage the data within the portal itself. This is incredibly useful in seeing what information is in a new dataset and playing with it a bit to see how useful it might be.

That said, the portal is still plagued by some familiar problems. For one, there are tons of datasets here, but only some of them seem to contain meaningful information. Opening up the City Clerk performance metrics, the data seems to trail off as the timeline goes on, like a New Year’s resolution that’s fallen by the wayside. Bad tracking means bad open data.

As a user with only minimal data experience, New York’s open data portal presents some serious challenges for the citizen user.

How do I find what I care about?

The more dataset s a government body displays, the harder it can be to sort through them to find one you think is interesting. Search is made more challenging by the decision, by many of the cities I looked at, to organize open data in the same arcane way the government itself is organized. An “Education” bucket makes intuitive sense, but what does Seattle mean by “City Business” or “Land Use”? Interestingly, LA adds another potential filter — by policy priority. You can filter datasets by “A safe city,” “a well run city, “a liveable and sustainable city,” and “aa prosperous city.” While these categories are also a bit vague, I wonder if that framing and organization solves the focus problem, by helping users find and surface data in line with the city’s existing priorities?

What is this stuff?

I wanted to analyze the workings of the New York City Council, so I chose a dataset that listed all of the legislative items (resolutions, laws, etc.) introduced in the second half of 2014. Next, as the user, I’ve got to understand the workings of City Council before I make much sense of the data. I know what a “land use application” is, but what is a “land use call-up”? Are they related? If an item here seems to be stuck in the “Committee” status, how likely is it to leave that Committee?

The larger problem here is that open data portals are physically separated from other contextual information about how the government works. New York City Council does a pretty good job showing the process a new law goes through, from introduction to adoption — but that’s all on a separate part of the website. I now have to go searching for it, and then match up what I see in the dataset to the information that the Council provides on the website. In separating the data from its context, open data portals erect barriers for the average user. These barriers help ensure that only those who are really interested and informed will understand the data enough to parse it. This likely selects for government officials themselves (great) but not for many typical citizens, save those that are (for better or worse) obsessed with the arcana of City Council.

How do I work with it?

How does the average user know how to work with the data? Maybe she’s already a data geek, but the rest of us interested citizens will have to learn on the fly. In my case, some of the work of teaching fell to the Tableau software itself, where I turned to learn not just how to use the software, but their basic best practices for creating visualizations. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get any of 3 downloads of Tableau to work, so resorted to Excel.

If even someone like me who went into this assignment wanting to try out Tableau resorted in the end to really simple graphs in Excel, I can only imagine what users with less time on their hands would do. The length of time, and amount of skill needed, drove home to me the realization that few average citizens are logging on to data portals just to have a go, and if they are, they’re likely not producing anything meaningful. The real users are those with the resources: civic hackers, journalists interested in uncovering city problems, and interest groups with research staff.

How do I determine good behavior?

Now that I can start playing with the data, I need to figure out what I’m trying to ensure the government does. Open data about service delivery may be fairly clear cut, but measuring the performance of City Council processes is a bit harder. What’s the normal length for a proposed law to be in Committee? Are there both productive and unproductive reasons that laws would stay in Committee? How do New York’s time frames for passing laws compare to other cities’? And are quick timeframes even desirable — or are they a sign of not fully exploring each issue?

It’s hard for the average user to decide these normative questions. And it’s hard for the government itself to tell us what to care about. Sure, they can have a city or mayoral dashboard that aggregates the metrics they think are important. But open data portals are by nature less prescriptive. Governments are too impartial to impose any significant normative structure on the data — and, after all, part of the benefit in releasing data is to surface new normative judgments that the government hasn’t already realized.

What we need are some sort of impartial proxy between the government and citizens, to provide more context and more conscience. Investigative journalists like Pro Publica might serve this need a bit; they think of themselves as working in the public interest, and some of their open data projects help us find and contextualize information. I wonder if the rise of open data portals will create a more diverse market of entities that can help decode data.

All in all, after several hours of work, I had 2 fairly lame Excel charts to show for it.

My experiences convinced me that, despite the rosy pictures governments might paint, few average citizens are firing up their computers, downloading CSV files, and teaching themselves Excel. The real users of these systems are likely more educated, well-connected, and potentially self-interested.

Let’s not jump on the Lastpass bandwagon just yet

Should a 15,000-employee organization adopt LastPass? On the one hand, LastPass seems to bring clear benefits, not just in improving overall security, but in reframing the importance of employees’ own security behaviors. On the other hand, mandating Lastpass means considering the tradeoffs of time, resources, and accessibility.

These tradeoffs require us to assess the company’s particular needs — goals, vulnerabilities, and approaches — in order to make the final decision.

Benefits

The benefits of employees using Lastpass are fairly clear. Lastpass use would reduce the chances that a threat can work its way from an individual account to threaten the entire network. The status quo of decentralizing security choices to each individual employee is dangerous because the system is only as strong as its weakest link. Mandating Lastpass use across the company would eliminate these weak links in password security.

Moreover, the process of instituting Lastpass may have positive reframing effects for individuals. While spending the time to change their passwords into Lastpass — and wondering why the company cares about their security in this way — employees would be encouraged to see their own security practices as part of the larger system of the company’s security. Helping employees see themselves within the system likely has positive network effects further down the line, when individual has to make security decisions and takes their role in the network into consideration.

Drawbacks & Tradeoffs

But it’s not all rainbows and unicorns. One obvious tradeoff is staff time. We could estimate that it would take the average employee one hour to get signed up and transfer the accounts to the new system. Thinking on a system level, the Lastpass mandate then requires 15,000 hours of company time (375 work weeks of time), in addition to the administrative time to communicate and guide employees in changing to the new system. This is no small decision.

Thinking on the broader level of security, there’s likely some sort of finite amount of security resources the company can spend. The company’s IT & Security Teams have finite time and budget to implement projects; employees and managers have finite patience for instituting new security measures. Overall, choosing to implement Lastpass will likely mean not implementing another security improvement. This tradeoff makes it important to judge the Lastpass mandate in the context of other possible security upgrades. Is password security the best place to invest these resources?

Another tradeoff to consider is usability or accessibility versus security. While Lastpass is not too overwhelming of a system, it will change how employees interact with the network, how efficient they are, and how easy their work is. Does mandating Lastpass privilege the needs of the system over the needs of the employees?

Given that Lastpass is not completely intuitive, it’s also possible for employees to subscribe to the system without following certain best practices. For instance, it seems possible to use the same password for multiple sites, but to store that password in Lastpass. So in the messiness of practice, mandating Lastpass does not necessitate high password security. There’s also a slight risk that Lastpass will provide employees with the veneer of security while distracting them from larger security concerns — that people will feel safer without being safer.

Making the decision

What are we to do with these tradeoffs? A decision should be based on both an understanding of the system’s structure and a realistic threat model.

In this case, understanding the system’s structure would mean understanding more about how employees’ computers and accounts are connected to each other. What kind of network is at play in the services employees use? How interconnected are users and services? What data is stored where?

Building a realistic threat model would take some introspection. What are the goals of security at the company: simply to protect company security? Or is there other personal data the company collects? Does the company have a responsibility to the public — as a whole or as individuals — for any of the data in its hands?

What are the system’s vulnerabilities? How big of a problem is lax password security by individuals, compared to other vulnerabilities to the system? Are there malicious actors who might be able to break the system’s walls? Would Lastpass prevent or lessen the effect of those attacks?

Finally, are there countermeasures other than Lastpass that might be better suited to these goals and vulnerabilities? Does the company really need to collect the personal information it collects? Can it identify or measure threats using testing and agile development, rather than assuming we know their likelihood and consequences?

Absent context, mandating Lastpass approval seems like an objective improvement to company security. But the decision to do so requires understanding the tradeoffs between costs and benefits. Hopefully, the understanding necessary to make this decision will benefit the company more broadly, by helping it understand its security needs, threats, and options on a holistic level.

A Foray into Wikipedia Editing

With Wikipedia’s “Bold but not reckless” rule in mind, I made small (but I think important!) edits to the page on Participatory Budgeting (username: pb&jelly).

Why Participatory Budgeting?

After a summer working on Participatory Budgeting (PB) with the New York City Council, I know and care about the topic. PB is a concept many people haven’t heard of, so its Wikipedia page is an important “first impression” point. The page as I found it was confusing and overly technical. Page view history shows a spike in early September, which coincides with the startup of the New York’s PB process. I can just picture residents getting an email from their Council Member or seeing a flyer and turning to Wikipedia to figure out what PB is — and I want them to have a better chance of getting it.

Wikipedia and PB are both participatory processes designed to include a large number of voices in decision-making. I think it’s important that the Wikipedia article about PB take advantage of this congruence to make more information accessible. Since PB is a community-owned process, sources like the New York City Council shouldn’t have a monopoly on information about PB for New York residents. And those living in areas without PB processes should be able to find out more about how the process works. Figuring out what, and how much, to share was the next challenge.

Wikipedia as history lesson

Looking through the history of edits on the page, the basic information structure really hasn’t changed over time. In contrast, the phenomenon of PB has grown exponentially since its Wikipedia page was first created.

That original structure is quite heavy on PB’s origins in Porto Alegre, Brazil. This makes a lot of sense as a decision in 2005. It still makes some sense in 2016, but it’s surprising how big of an effect these early decisions still have on the presentation of information. And at this point, the Porto Alegre case is useful as a historical origin story, not as the single example it once was. I’m curious to see whether this overall structure will ever change to limit the Brazilian background — and whether that will represent a “forgetting” of where the process has come from, or a reworking of the history that’s important to it.

What should people know about this, anyway?

In deciding what information I thought people should know about PB, I tried to picture a typical user of the page (“Know your audience”!). I imagined them (as biased towards New York as I am) as NYC residents shown a PB advertisement, potentially the kind of person the PB process is really focused on involving — low-income or marginalized residents with little access to other channels of political power. The current page was written in a formal, vague language (“PB has the potential to provide social inclusion and social equity in the decision making of the allocation of resources in communities with low socioeconomic statuses.”) — so I attempted to make it more concrete and readable (“PB processes are typically designed to involve those left out of traditional methods of public engagement, such as low-income residents, non-citizens, and youth.)

In addition to fleshing out the section on NYC, I decided to add information on the PB processes in Boston and Paris, on the idea that these examples show how the process can run differently in different places. I also wanted to give the reader a sense of how the phenomenon of PB is growing and changing over time.

The humans behind it all

But who’s to say that’s the right combination of information, or the right narrative? Editing the page, it’s clear just how human all these decisions are. I, for one, am biased to think the NYC example is super fascinating and important, and to ignore everything else. Sure, it’s a bunch of different humans, editing each other over time, but on a page that doesn’t attract a ton of attention, that’s still a small group. I’ve talked to a few of the people mentioned in the citations. Are any of them involved in editing the page? What agendas do the other editors have? How are we each using this Wikipedia page as forum for working out identity and ego issues and other conflicts? And what will happen from here on out?

Thinking Like a Platform

Back when I worked at a petition website, our Executive Team decided one day that we should be calling ourselves a platform, not a website. At the time, I had only a vague idea of what that change meant or why it was important. It had something to do with future possibilities, with how we saw the potential for the website. Beyond that, it was a word everyone else was using, so we had to get on board.

So what is a platform?

Looking back now, it’s clear that a platform is a shared foundation – of technologies, standards, infrastructure, and even users – on which other developers and users can build. Their magic is that by providing this foundation, platforms reduce the costs for others to create value in that same space. This creation often takes place outside the purview of the original design, outside the control of the platform builders. The platform is just the beginning of the possible.

We can think of platform thinking, then, as a mode of design in which you consider not only your own organization’s needs, but broader, hypothetical sets of users and use cases. Ideally, platform creators think ahead to how their database or tool might be used by future developers, and they design the platform in a way that enables that creation.

Why should we care about platforms?

Platforms punch above their weight by creating new layers of opportunity – and this multiplying effect makes them fascinating. The result is more, faster, and broader creativity.

Existing platforms matter to the government because they can often reach the kind of scale traditionally reserved for governments and government-sanctioned monopolies. This may either threaten the power of a government, or provide an additional, alternative public service.

More importantly, governments should care not just about platforms, but about platform thinking. Currently, government services are created and delivered one by one. Governments aren’t incentivized to simplify, cooperate between departments, or find economies of scale, particularly where budgeting and planning are decided department by department. Porting platform thinking over introduces a new model of government: government as platform, as “convener and enabler.”

It’s an exciting model because decentralizing power leads to much more innovation – and that innovation is likely better – more useful, quicker, and more efficient than it would have been had it been under complete control of the government, who can only predict so many uses for its own tools. Platform thinking also makes it easier for users, because it acknowledges separate government services as part of a cohesive whole the user must interact with. For instance, this model of thinking would encourage governments to reduce friction between similar systems. It would call governments to publish open data in useable form, or to build tools in a way that helps nonprofit partners use them.

Who has the power?

Platforms both create new power imbalances and perpetuate old structures of power. In giving up some of their own centralized control, platforms implicitly give power to those who build on top of them. While they set some standards and regulations, platforms usually can’t control exactly how people use the platform. The platform, in turn, is then controlled somewhat by those other players. If the platform changes, those players may not be able to play. It may well be in the interests of the platform to keep those players happy, and thus be somewhat constrained in their own work.

But of course platforms also exert a lot of control over the ecosystems they create. Because of their increased ability to scale to more users, platforms can become monopolistic, both horizontally (eating up huge portions of potential users) and vertically (fulfilling a wide range of their needs). They may achieve this monopoly without pressuring users, but their services are just so widespread and widely used that it becomes very hard not to be another user. I’m guessing my aunt, who rarely turns her computer on, is the only person I know who doesn’t use Google regularly. And when everyone uses them, that user lock-in minimizes competition further. Only if most people I know left Facebook for Google+ would I transition over. While user bases might decide to make that transition en masse – witness the MySpace to Facebook migration – individual users are a bit more stuck.

This monopolistic outcome can be problematic. Should private companies have that much power over our lives? And if they’re really providing basic services, should they be regulated like water? The Net Neutrality battle over how much control internet providers has set such a precedent. Simultaneously, platforms can exploit their appearance as utilities, as in the case of Facebook offering a “free” version of the internet, based closely on Facebook access, to developing countries.

To the extent that scale doesn’t necessitate accessibility, platforms may repeat structural power imbalances in ways that are hard to spot. When everyone I know uses Google, I forget about the large pockets of the world on the other side of a digital divide, who lack internet access, tools, or fluency in using this now “basic” service. Scale gives the illusion of openness.

Finally, platforms encourage power imbalances to the extent that layers of platforms become invisible to us. Invisible parts of the platform can be controlled more easily because they start to seem inevitable, magical, part of the infrastructure. As creators of Facebook content, we can forget that the platform itself is continually being created under us, that the Trending feature was not just a service provided by an algorithm but a process of creation marked by human choices. The invisibility of appearing to be part of the foundation itself can be quite dangerous.

Where should government go from here?

Interestingly, internet platforms already borrow from the government model to think about their own governance. At my old workplace, we used to compare our user base to that of the government of Germany. Like a country, the needs of a platform’s users are diverse and interlocking.

Clearly, the models of government and platform go well hand-in-hand. If governments can get that combination working, they can stay in control where it matters – while providing better service and spurring innovation.

Customer Profile of a Voter

What is it like to be a voter?

Shiny New Spreadsheets

When my boss explained his new idea about tracking individual performance metrics, it seemed like a great idea.

Our 15-person team of Communications Directors engaged in a wide variety of activities — meeting journalists, pitching stories, designing media strategies for clients — and not every activity led to a tangible outcome. Directors might work for months to build a relationship with a key journalist, only to realize that the outlet wouldn’t run the piece at all. Nevertheless, this behind-the-scenes work was crucial to building the company’s brand.

Recently, a few team members had complained that they weren’t getting credit for all this unseen work. Shouldn’t their performance be measured on whether they targeted and pitched journalists in smart ways — not whether they were lucky in landing stories?

My boss’ solution? A point system in which both activities and outcomes were added up to a score. Team members would need to record all their activities — meetings, events, pitches, and the rest. By quantifying a performance score, both they and my boss could look at performance changes from quarter to quarter and year to year.

As his assistant, I took over project management of this spreadsheet and was soon coming up with all sorts of formulas to calculate a total score. The end result was a personalized spreadsheet with several tabs calculating each activity and a summary tab to look at scores over time.

It was a disaster.

What had started as an attempt to give Directors “credit” had turned into a system for micromanaging their movements. As they recorded each media mention, meeting, and event, they wondered why their boss didn’t trust them to do the basic work of their jobs. Why all the hand-holding? And instead of being able to give them “credit,” we felt like Big Brother. We used the tracking system for another six months, until my boss thought of a better system and everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

Looking back on this episode, there are several reasons I think we failed, both in conceiving the project and in iterating on it once it became clear the spreadsheet wasn’t working. The concepts of user design and iterated testing are particularly useful frameworks for analyzing these mistakes.

At the time, we thought we were being user-centric. Someone had raised a problem, and we were building a spreadsheet to solve it! What a responsive management team! But because we didn’t do our user research well, in reality we were using this “user problem” as an excuse for our own end goals of more insight into Directors’ work.

How we messed it up

Extrapolating a large problem from a few complaints

Two out of our 15 team members had complained. Was that evidence of a pattern, or had we simply found outliers? We didn’t bother to find out. Surely all Directors needed the same tools to do their jobs!

Failing to consider the “pivot” or “perish” options

Since the spreadsheet was my boss’ brilliant new idea, we never tested its basic premise. Would tracking all their activities help Directors feel more acknowledged? Would it create any new problems?

It was pretty clear from the beginning that the new metrics tracker wasn’t taking off. In fact, it was leading to less insight into Directors’ work, as they felt less trusted and became more cagey about their activities. But we didn’t change the system for another six months — and only then because my boss had thought of a better idea. With his spreadsheet idea on the line, we couldn’t change until he had thought of a better idea. This meant limited input from others who might have had better ideas, while we waited for a busy manager to think of a better idea.

Our attempt to solve a user’s concern had turned into a project to prove ourselves. The result was a system designed for us but passed off as a solution for them.

Questioning our users’ motives

That’s not to say that we didn’t consult Directors. But instead of asking our users what they wanted out of a metrics tracker, we presented them with the unfinished spreadsheet and asked them how they liked it. Naturally, they said it was overly complicated and overwhelming. “I just don’t think it’ll work,” one said. Taking the spreadsheet as a given, we took the negative feedback as a sign we needed to reduce the spreadsheet’s complexity, not go back to the drawing board. All our further “testing” revolved around how to make the spreadsheet easier to use.

Given that the tracker was a performance measurement tool, it was easy to dismiss negative feedback as staffers being concerned that a change would lead to unfairly bad performance reviews for them. What if this “score” just didn’t add up fairly? they asked. No, no, no, we assured them. We’ll tinker with this score formula until it works! All we want is to give you is a fair outcome for all this work you’re doing!

Technology for technology’s sake

Perhaps worst of all, this issue probably didn’t need the “technology” of the spreadsheet at all. Thinking back on this episode, the “not getting credit” complaint likely hid a deeper problem — one that may well not have been about metrics at all. Were they feeling insecure? Overworked? Ineffective? All of these would be reasons to complain about a lack of acknowledgement; none of them were best served by a flashy new spreadsheet. In fact, the spreadsheet likely exacerbated the underlying issues of trust that the Directors were surfacing in their complaint.

How I would do it all over

If I could do it all over, I would dig deeper into the underlying issues behind these complaints. Rarely is a user able to articulate exactly what he or she really needs, particularly without further questioning. We shouldn’t have taken an offhand complaint as license to develop a months-long project, without exploring the issue more.

But assuming that we then decided to redesign the metrics system — and that we wanted to solve a user problem, rather than mandating our own version of metrics collection — I would have come up with a scheme for gradual testing of the concept and then the design.

The first step would be to talk to the two Directors who complained, as well as others who hadn’t. What did they look for in a metrics tool? What kinds of features helped them plan and improve their work? The next phase could test out the spreadsheet score system as an idea. Were we to come up with a spreadsheet that calculated a metrics score, would that be useful to you in getting credit from your boss? What activities should be added into that score? Next, it would be useful to ask a few Directors to record their activities for a week on paper or a simplified spreadsheet. If they stopped tracking by the end of the week, that might be a warning sign that a system of tracking would be hard to keep up with. No matter how simplified the spreadsheet got, it wasn’t simpler than writing it on a piece of paper. So if this test in particular failed, we should strongly have considered scrapping the idea.

All these steps would expand the solution-creating team from my boss and me to our full team. The key would be to avoid attaching my boss’ reputation to the spreadsheet as the solution. Had we tested the idea before presenting it as the solution, we could have separated the success of the spreadsheet from the success of my boss’ management more broadly. This would have allowed us to scrap the idea altogether — or to change it significantly to make it work.

We could have built a system that worked for us, focusing on getting buy-in and building a case for our system. Or we could have actually paid attention to our users and tried to solve their problem, thus building trust with our users. Believing — and insisting — that we were solving a user problem while pushing through our own vision was a surefire way to break that trust.

First blog post

This is your very first post. Click the Edit link to modify or delete it, or start a new post. If you like, use this post to tell readers why you started this blog and what you plan to do with it.