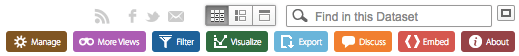

First, to sing a few praises: New York City’s Open Data portal has more than 1500 datasets available, and their tool allows you to sort, filter, and manage the data within the portal itself. This is incredibly useful in seeing what information is in a new dataset and playing with it a bit to see how useful it might be.

That said, the portal is still plagued by some familiar problems. For one, there are tons of datasets here, but only some of them seem to contain meaningful information. Opening up the City Clerk performance metrics, the data seems to trail off as the timeline goes on, like a New Year’s resolution that’s fallen by the wayside. Bad tracking means bad open data.

As a user with only minimal data experience, New York’s open data portal presents some serious challenges for the citizen user.

How do I find what I care about?

The more dataset s a government body displays, the harder it can be to sort through them to find one you think is interesting. Search is made more challenging by the decision, by many of the cities I looked at, to organize open data in the same arcane way the government itself is organized. An “Education” bucket makes intuitive sense, but what does Seattle mean by “City Business” or “Land Use”? Interestingly, LA adds another potential filter — by policy priority. You can filter datasets by “A safe city,” “a well run city, “a liveable and sustainable city,” and “aa prosperous city.” While these categories are also a bit vague, I wonder if that framing and organization solves the focus problem, by helping users find and surface data in line with the city’s existing priorities?

What is this stuff?

I wanted to analyze the workings of the New York City Council, so I chose a dataset that listed all of the legislative items (resolutions, laws, etc.) introduced in the second half of 2014. Next, as the user, I’ve got to understand the workings of City Council before I make much sense of the data. I know what a “land use application” is, but what is a “land use call-up”? Are they related? If an item here seems to be stuck in the “Committee” status, how likely is it to leave that Committee?

The larger problem here is that open data portals are physically separated from other contextual information about how the government works. New York City Council does a pretty good job showing the process a new law goes through, from introduction to adoption — but that’s all on a separate part of the website. I now have to go searching for it, and then match up what I see in the dataset to the information that the Council provides on the website. In separating the data from its context, open data portals erect barriers for the average user. These barriers help ensure that only those who are really interested and informed will understand the data enough to parse it. This likely selects for government officials themselves (great) but not for many typical citizens, save those that are (for better or worse) obsessed with the arcana of City Council.

How do I work with it?

How does the average user know how to work with the data? Maybe she’s already a data geek, but the rest of us interested citizens will have to learn on the fly. In my case, some of the work of teaching fell to the Tableau software itself, where I turned to learn not just how to use the software, but their basic best practices for creating visualizations. Unfortunately, I couldn’t get any of 3 downloads of Tableau to work, so resorted to Excel.

If even someone like me who went into this assignment wanting to try out Tableau resorted in the end to really simple graphs in Excel, I can only imagine what users with less time on their hands would do. The length of time, and amount of skill needed, drove home to me the realization that few average citizens are logging on to data portals just to have a go, and if they are, they’re likely not producing anything meaningful. The real users are those with the resources: civic hackers, journalists interested in uncovering city problems, and interest groups with research staff.

How do I determine good behavior?

Now that I can start playing with the data, I need to figure out what I’m trying to ensure the government does. Open data about service delivery may be fairly clear cut, but measuring the performance of City Council processes is a bit harder. What’s the normal length for a proposed law to be in Committee? Are there both productive and unproductive reasons that laws would stay in Committee? How do New York’s time frames for passing laws compare to other cities’? And are quick timeframes even desirable — or are they a sign of not fully exploring each issue?

It’s hard for the average user to decide these normative questions. And it’s hard for the government itself to tell us what to care about. Sure, they can have a city or mayoral dashboard that aggregates the metrics they think are important. But open data portals are by nature less prescriptive. Governments are too impartial to impose any significant normative structure on the data — and, after all, part of the benefit in releasing data is to surface new normative judgments that the government hasn’t already realized.

What we need are some sort of impartial proxy between the government and citizens, to provide more context and more conscience. Investigative journalists like Pro Publica might serve this need a bit; they think of themselves as working in the public interest, and some of their open data projects help us find and contextualize information. I wonder if the rise of open data portals will create a more diverse market of entities that can help decode data.

All in all, after several hours of work, I had 2 fairly lame Excel charts to show for it.

My experiences convinced me that, despite the rosy pictures governments might paint, few average citizens are firing up their computers, downloading CSV files, and teaching themselves Excel. The real users of these systems are likely more educated, well-connected, and potentially self-interested.